Reflections on the Marshall Plan

Henry Kissinger recalls when George C. Marshall, speaking at Harvard’s Commencement in 1947, extended America’s hand to a battered Europe, helping to create a stable postwar order

In June 1947, Gen. George C. Marshall — revered as the “organizer of victory” and Army Chief of Staff during World War II and now five months into his tenure as President Harry S. Truman’s Secretary of State — addressed the Commencement audience in Harvard Yard. Describing the devastation of Europe’s economies and societies, Marshall pledged the United States would do “whatever it is able” to help rebuild the continent and restore its “normal economic health,” without which there could be “no political stability and no assured peace” throughout the world.

His speech marked a historic departure in American foreign policy.

Marshall invoked no self-deprecating anecdotes or poetic metaphors to illustrate the importance of the occasion. Not for him were adjectives to describe the attributes the graduating students were expected to display. Duty was its own justification; it could only be impaired by embellishment.

After a brief preface recalling that, as the graduates knew well, “the world situation is very serious,” Marshall outlined “the requirements for the rehabilitation of Europe.” Rarely looking up from the text he had carried to the podium in his jacket pocket, he offered a revolution in American foreign policy in the guise of a practical economic program. Toward the end of the speech, he apologized for entering into a “technical discussion” that had likely bored his listeners. Indeed, Commencement attendees, including Harvard President James B. Conant, would later confess they had not immediately understood the historical significance of what Marshall had outlined. He had in fact proposed a new design for American foreign policy.

“Marshall’s premise was straightforward: Economic crisis, he observed, produced social dissatisfaction, and social dissatisfaction generated political instability,” writes Henry A Kissinger. File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Marshall’s premise was straightforward: Economic crisis, he observed, produced social dissatisfaction, and social dissatisfaction generated political instability. The dislocations of World War II posed this challenge on a massive scale. European national debts were astronomical; currencies and banks were weak. The railroad and shipping industries were barely functional. Mines and factories were falling apart. The average farmer, unable to procure “the goods for sale which he desires to purchase,” had “withdrawn many fields from crop cultivation,” creating food scarcity in European cities.

At the same time, a political and strategic challenge to democratic societies had come into being. Moscow established Communist dictatorships in every territory its forces occupied at the close of the war — up to the River Elbe in the center of historic Europe. Beyond the satellite states, Soviet-backed political factions were probing Western Europe’s political cohesion. To safeguard their political future, European democracies needed, above all, to restore hope in their economic prospects. “The remedy,” Marshall offered, was a partnership between the United States and its European allies to rehabilitate “the entire fabric” of their economies. To address the most immediate crisis, America would send its friends food and fuel. Later, it would subsidize modernizing and expanding industrial centers and transportation systems.

Marshall’s so-called “technical discussion” was in fact a clarion call to a permanent role for America in the construction of international order. Historically, Americans had regarded foreign policy as a series of discrete challenges to be solved case by case, not as a permanent quest. At the conclusion of World War I, domestic support for the fledgling League of Nations foundered and the country turned inward. Declining to involve itself in the latent crises in Europe, American isolationism contributed to the outbreak of World War II. But America’s traditional attitude was up for debate again following the Allied victory.

In his speech at Harvard, Marshall put an end to isolationist nostalgia. Declaring war on “desperation and chaos,” he invited the United States to take long-term responsibility for both restoring Western Europe and recreating a global order.

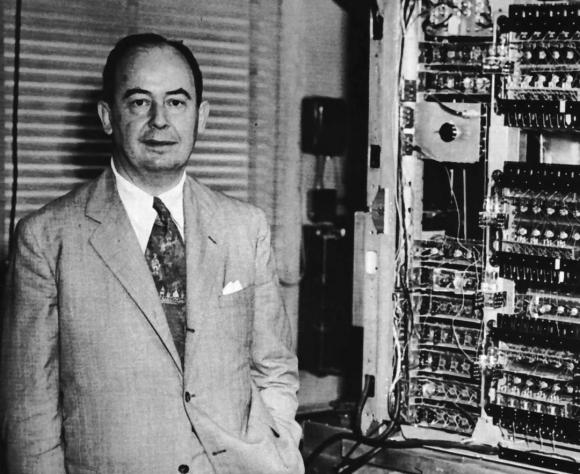

George C. Marshall on Commencement Day, 1947

Secretary of State George C. Marshall announced The Marshall Plan on Commencement Day 1947 in Harvard Yard.

Many of the Marshall Plan’s proposals were based on lessons learned in overcoming the depression of the 1930s by closing the gap between economic expectations and reality in America. In that sense, the plan represented the global application of the New Deal. But it succeeded because it transformed common necessities into partnership. Marshall stressed that it would be “neither fitting nor efficacious” for America to try to direct Europe’s economic recovery “unilaterally.” Common objectives were necessary — and they had to reflect a broader vision of political order for Europe, the Atlantic region and, ultimately, the world. The Marshall Plan inspired a new international order by enabling the nations of Europe first to rediscover their own identities in its pursuit, then to go on to build systems transcending national sovereignty, such as the Coal and Steel Community and, eventually, the European Union.

Luckily, Europe had leaders whose formative experience predated World War I, the most blighting impact of which was the continent’s loss of confidence in itself. But Konrad Adenauer (in Germany), Alcide De Gasperi (in Italy), and Robert Schuman (in France) had preserved the conviction that had characterized Europe’s life before these self-inflicted catastrophes. They viewed their challenge not in technical terms, but as the fulfilment of a political vision based on a common cultural heritage.

To British Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin, the Marshall Plan was “a lifeline to sinking men” that brought “hope where there was none” by giving recipients permission not only to overcome their present difficulties, but to imagine their future prosperity in cooperation with the United States. Paul-Henri Spaak, the Prime Minister of Belgium, called it “a striking demonstration of the advantages of cooperation between the United States and Europe, as well as among the countries of Europe themselves.” For this reason, French Foreign Minister Georges Bidault said, “The noble initiative of the Government of the United States is for our peoples an appeal which we cannot ignore.” And Dutch Foreign Minister Dirk Stikker anticipated the plan’s far-reaching impact, saying, “Churchill’s words won the war, Marshall’s words won the peace.”

Not the least significant aspect of Marshall’s speech was that it facilitated Germany’s reentrance into the community of nations as an equal partner. This is why in 1964, Adenauer, concluding his tenure as West German Chancellor, praised Truman for extending the plan’s provisions to Germany “in spite of her past.” The Marshall Plan, Adenauer said, made Germany “equal” to “other suffering countries,” countering for the first time the notion among the Allied powers “simply to efface Germany from history.” The plan gave Germany economic assistance but, more importantly, “new hope.” “Probably for the first time in history,” Adenauer said of Marshall’s speech, “a victorious country held out its hand so that the vanquished might rise again.”

An ingenious aspect of Marshall’s design was that aid was offered to all Europe, including the Soviet Union and its occupied satellites. Some of them — especially Czechoslovakia — were tempted. But Soviet leader Joseph Stalin rejected the offer on ideological grounds. He denounced the plan as economic imperialism — a “ploy” to “infiltrate European countries” — and forced his satellites to follow suit, thereby defining the fault lines along which the basic Cold War strategy of containment was to occur. As Moscow forcibly imposed its ideology on its sphere of influence, the Marshall Plan’s goals merged into a broader political one: the expansion of the concept of human dignity as a universal principle, and self-reliance as the recommended method of promoting it. While the Soviet system eroded gradually, Adenauer, De Gasperi, and Schuman helped to inspire the formation of the North Atlantic Alliance, the European Coal and Steel Community and, with the passage of decades, the European Union.

Every generation requires a vision before it can build its own reality. But no generation can rest on the laurels of its predecessors; each needs to make a new effort adapted to its own conditions. In Europe, the Marshall Plan helped consolidate nations whose political legitimacy had evolved over centuries. Once stabilized, those nations could move on to designing a more inclusive, cooperative order.

But subsequent generations occasionally took too literally Marshall’s description of the plan as “technical,” emphasizing its economic aspects above all else. In the process, they ran the risk of missing its political, indeed its spiritual, component. When America engaged in nation building in other countries, it found that political legitimacy had different foundations. As the United States tried to establish international order beyond Europe, economies remained vital. But the resolution of civil conflicts followed a rhythm beyond, and more complicated than, economic development. At times, attempts to apply literally the maxims of the Marshall Plan fractured the unity of America at home. Civil wars cannot be ended by economic programs alone. They must be transcended by a more comprehensive political vision.

The complexity of this challenge gives Marshall’s speech new significance today. In a moment of crisis, he stood up, boldly outlining a vision of reconciliation and hope and calling on the West to have the courage to transcend national boundaries. Now, the challenge of world order is even wider. Instead of strengthening a singular order on a continent with established political systems, the task has become global. The challenge is to devise a system in which a variety of societies can approach common problems in a way that unites their diverse cultures. This is why there is a special significance for the sons and daughters of Harvard of a speech delivered almost two generations ago. Universities are the residuaries of cultures and, in a way, the bridge between them. Twin calls to duty have emerged after almost 70 years from Marshall’s Commencement speech: that America should cultivate, with Western Europe, a vital Atlantic partnership; and that this partnership should fulfill its meaning by raising its sights to embrace the cultures of the universe.

Henry A. Kissinger ’50, A.M. ’52, Ph.D. ’54, and a former Harvard professor, was U.S. secretary of state from 1973 to 1977. A recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1973, he has authored more than a dozen books on foreign policy, international affairs, and diplomatic history.