Deep Learning

With massive amounts of computational power, machines can

now recognize objects and translate speech in real time. Artificial

intelligence is finally getting smart.

AI這 行業採用的術語似乎很誇張 譬如說所謂的 Deep Learning

«

Deep Learning

With massive amounts of computational power, machines can

now recognize objects and translate speech in real time. Artificial

intelligence is finally getting smart.

»

When Ray Kurzweil met with Google CEO Larry Page last

July, he wasn’t looking for a job. A respected inventor who’s become a

machine-intelligence futurist, Kurzweil wanted to discuss his upcoming

book How to Create a Mind. He told Page, who had read an early

draft, that he wanted to start a company to develop his ideas about how

to build a truly intelligent computer: one that could understand

language and then make inferences and decisions on its own.

It quickly became obvious that such an effort would require nothing

less than Google-scale data and computing power. “I could try to give

you some access to it,” Page told Kurzweil. “But it’s going to be very

difficult to do that for an independent company.” So Page suggested that

Kurzweil, who had never held a job anywhere but his own companies, join

Google instead. It didn’t take Kurzweil long to make up his mind: in

January he started working for Google as a director of engineering.

“This is the culmination of literally 50 years of my focus on artificial

intelligence,” he says.

Kurzweil was attracted not just by Google’s computing resources but

also by the startling progress the company has made in a branch of AI

called deep learning. Deep-learning software attempts to mimic the

activity in layers of neurons in the neocortex, the wrinkly 80 percent

of the brain where thinking occurs. The software learns, in a very real

sense, to recognize patterns in digital representations of sounds,

images, and other data.

The basic idea—that software can simulate the neocortex’s large array

of neurons in an artificial “neural network”—is decades old, and it has

led to as many disappointments as breakthroughs. But because of

improvements in mathematical formulas and increasingly powerful

computers, computer scientists can now model many more layers of virtual

neurons than ever before.

With this greater depth, they are producing remarkable advances in

speech and image recognition. Last June, a Google deep-learning system

that had been shown 10 million images from YouTube videos proved almost

twice as good as any previous image recognition effort at identifying

objects such as cats. Google also used the technology to cut the error

rate on speech recognition in its latest Android mobile software. In

October, Microsoft chief research officer Rick Rashid wowed attendees at

a lecture in China with a demonstration of speech software that

transcribed his spoken words into English text with an error rate of 7

percent, translated them into Chinese-language text, and then simulated

his own voice uttering them in Mandarin. That same month, a team of

three graduate students and two professors won a contest held by Merck

to identify molecules that could lead to new drugs. The group used deep

learning to zero in on the molecules most likely to bind to their

targets.

Google in particular has become a magnet for deep learning and

related AI talent. In March the company bought a startup cofounded by

Geoffrey Hinton, a University of Toronto computer science professor who

was part of the team that won the Merck contest. Hinton, who will split

his time between the university and Google, says he plans to “take ideas

out of this field and apply them to real problems” such as image

recognition, search, and natural-language understanding, he says.

All this has normally cautious AI researchers hopeful that

intelligent machines may finally escape the pages of science fiction.

Indeed, machine intelligence is starting to transform everything from

communications and computing to medicine, manufacturing, and

transportation. The possibilities are apparent in IBM’s Jeopardy!-winning

Watson computer, which uses some deep-learning techniques and is now

being trained to help doctors make better decisions. Microsoft has

deployed deep learning in its Windows Phone and Bing voice search.

Extending deep learning into applications beyond speech and image

recognition will require more conceptual and software breakthroughs, not

to mention many more advances in processing power. And we probably

won’t see machines we all agree can think for themselves for years,

perhaps decades—if ever. But for now, says Peter Lee, head of Microsoft

Research USA, “deep learning has reignited some of the grand challenges

in artificial intelligence.”

Building a Brain

There have been many competing approaches to those challenges. One

has been to feed computers with information and rules about the world,

which required programmers to laboriously write software that is

familiar with the attributes of, say, an edge or a sound. That took lots

of time and still left the systems unable to deal with ambiguous data;

they were limited to narrow, controlled applications such as phone menu

systems that ask you to make queries by saying specific words.

Neural networks, developed in the 1950s not long after the dawn of AI

research, looked promising because they attempted to simulate the way

the brain worked, though in greatly simplified form. A program maps out a

set of virtual neurons and then assigns random numerical values, or

“weights,” to connections between them. These weights determine how each

simulated neuron responds—with a mathematical output between 0 and 1—to

a digitized feature such as an edge or a shade of blue in an image, or a

particular energy level at one frequency in a phoneme, the individual

unit of sound in spoken syllables.

Some of today’s artificial neural networks can train themselves to recognize complex patterns.

Programmers would train a neural network to detect an object or

phoneme by blitzing the network with digitized versions of images

containing those objects or sound waves containing those phonemes. If

the network didn’t accurately recognize a particular pattern, an

algorithm would adjust the weights. The eventual goal of this training

was to get the network to consistently recognize the patterns in speech

or sets of images that we humans know as, say, the phoneme “d” or the

image of a dog. This is much the same way a child learns what a dog is

by noticing the details of head shape, behavior, and the like in furry,

barking animals that other people call dogs.

But early neural networks could simulate only a very limited number

of neurons at once, so they could not recognize patterns of great

complexity. They languished through the 1970s.

In the mid-1980s, Hinton and others helped spark a revival of

interest in neural networks with so-called “deep” models that made

better use of many layers of software neurons. But the technique still

required heavy human involvement: programmers had to label data before

feeding it to the network. And complex speech or image recognition

required more computer power than was then available.

Finally, however, in the last decade Hinton and other researchers

made some fundamental conceptual breakthroughs. In 2006, Hinton

developed a more efficient way to teach individual layers of neurons.

The first layer learns primitive features, like an edge in an image or

the tiniest unit of speech sound. It does this by finding combinations

of digitized pixels or sound waves that occur more often than they

should by chance. Once that layer accurately recognizes those features,

they’re fed to the next layer, which trains itself to recognize more

complex features, like a corner or a combination of speech sounds. The

process is repeated in successive layers until the system can reliably

recognize phonemes or objects.

Like cats. Last June, Google demonstrated one of the largest neural

networks yet, with more than a billion connections. A team led by

Stanford computer science professor Andrew Ng and Google Fellow Jeff

Dean showed the system images from 10 million randomly selected YouTube

videos. One simulated neuron in the software model fixated on images of

cats. Others focused on human faces, yellow flowers, and other objects.

And thanks to the power of deep learning, the system identified these

discrete objects even though no humans had ever defined or labeled them.

What stunned some AI experts, though, was the magnitude of

improvement in image recognition. The system correctly categorized

objects and themes in the YouTube images 16 percent of the time. That

might not sound impressive, but it was 70 percent better than previous

methods. And, Dean notes, there were 22,000 categories to choose from;

correctly slotting objects into some of them required, for example,

distinguishing between two similar varieties of skate fish. That would

have been challenging even for most humans. When the system was asked to

sort the images into 1,000 more general categories, the accuracy rate

jumped above 50 percent.

Big Data

Training the many layers of virtual neurons in the experiment took

16,000 computer processors—the kind of computing infrastructure that

Google has developed for its search engine and other services. At least

80 percent of the recent advances in AI can be attributed to the

availability of more computer power, reckons Dileep George, cofounder of

the machine-learning startup Vicarious.

There’s more to it than the sheer size of Google’s data centers,

though. Deep learning has also benefited from the company’s method of

splitting computing tasks among many machines so they can be done much

more quickly. That’s a technology Dean helped develop earlier in his

14-year career at Google. It vastly speeds up the training of

deep-learning neural networks as well, enabling Google to run larger

networks and feed a lot more data to them.

Already, deep learning has improved voice search on smartphones.

Until last year, Google’s Android software used a method that

misunderstood many words. But in preparation for a new release of

Android last July, Dean and his team helped replace part of the speech

system with one based on deep learning. Because the multiple layers of

neurons allow for more precise training on the many variants of a sound,

the system can recognize scraps of sound more reliably, especially in

noisy environments such as subway platforms. Since it’s likelier to

understand what was actually uttered, the result it returns is likelier

to be accurate as well. Almost overnight, the number of errors fell by

up to 25 percent—results so good that many reviewers now deem Android’s

voice search smarter than Apple’s more famous Siri voice assistant.

For all the advances, not everyone thinks deep learning can move

artificial intelligence toward something rivaling human intelligence.

Some critics say deep learning and AI in general ignore too much of the

brain’s biology in favor of brute-force computing.

One such critic is Jeff Hawkins, founder of Palm Computing, whose

latest venture, Numenta, is developing a machine-learning system that is

biologically inspired but does not use deep learning. Numenta’s system

can help predict energy consumption patterns and the likelihood that a

machine such as a windmill is about to fail. Hawkins, author of On Intelligence,

a 2004 book on how the brain works and how it might provide a guide to

building intelligent machines, says deep learning fails to account for

the concept of time. Brains process streams of sensory data, he says,

and human learning depends on our ability to recall sequences of

patterns: when you watch a video of a cat doing something funny, it’s

the motion that matters, not a series of still images like those Google

used in its experiment. “Google’s attitude is: lots of data makes up for

everything,” Hawkins says.

But if it doesn’t make up for everything, the computing resources a

company like Google throws at these problems can’t be dismissed. They’re

crucial, say deep-learning advocates, because the brain itself is still

so much more complex than any of today’s neural networks. “You need

lots of computational resources to make the ideas work at all,” says

Hinton.

What’s Next

Although Google is less than forthcoming about future applications,

the prospects are intriguing. Clearly, better image search would help

YouTube, for instance. And Dean says deep-learning models can use

phoneme data from English to more quickly train systems to recognize the

spoken sounds in other languages. It’s also likely that more

sophisticated image recognition could make Google’s self-driving cars

much better. Then there’s search and the ads that underwrite it. Both

could see vast improvements from any technology that’s better and faster

at recognizing what people are really looking for—maybe even before

they realize it.

Sergey Brin has said he wants to build a benign version of HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

This is what intrigues Kurzweil, 65, who has long had a vision of

intelligent machines. In high school, he wrote software that enabled a

computer to create original music in various classical styles, which he

demonstrated in a 1965 appearance on the TV show I’ve Got a Secret.

Since then, his inventions have included several firsts—a

print-to-speech reading machine, software that could scan and digitize

printed text in any font, music synthesizers that could re-create the

sound of orchestral instruments, and a speech recognition system with a

large vocabulary.

Today, he envisions a “cybernetic friend” that listens in on your

phone conversations, reads your e-mail, and tracks your every move—if

you let it, of course—so it can tell you things you want to know even

before you ask. This isn’t his immediate goal at Google, but it matches

that of Google cofounder Sergey Brin, who said in the company’s early

days that he wanted to build the equivalent of the sentient computer HAL

in 2001: A Space Odyssey—except one that wouldn’t kill people.

For now, Kurzweil aims to help computers understand and even speak in

natural language. “My mandate is to give computers enough understanding

of natural language to do useful things—do a better job of search, do a

better job of answering questions,” he says. Essentially, he hopes to

create a more flexible version of IBM’s Watson, which he admires for its

ability to understand Jeopardy! queries as quirky as “a long,

tiresome speech delivered by a frothy pie topping.” (Watson’s correct

answer: “What is a meringue harangue?”)

Kurzweil isn’t focused solely on deep learning, though he says his

approach to speech recognition is based on similar theories about how

the brain works. He wants to model the actual meaning of words, phrases,

and sentences, including ambiguities that usually trip up computers. “I

have an idea in mind of a graphical way to represent the semantic

meaning of language,” he says.

That in turn will require a more comprehensive way to graph the

syntax of sentences. Google is already using this kind of analysis to

improve grammar in translations. Natural-language understanding will

also require computers to grasp what we humans think of as common-sense

meaning. For that, Kurzweil will tap into the Knowledge Graph, Google’s

catalogue of some 700 million topics, locations, people, and more, plus

billions of relationships among them. It was introduced last year as a

way to provide searchers with answers to their queries, not just links.

Finally, Kurzweil plans to apply deep-learning algorithms to help

computers deal with the “soft boundaries and ambiguities in language.”

If all that sounds daunting, it is. “Natural-language understanding is

not a goal that is finished at some point, any more than search,” he

says. “That’s not a project I think I’ll ever finish.”

Though Kurzweil’s vision is still years from reality,

deep learning is likely to spur other applications beyond speech and

image recognition in the nearer term. For one, there’s drug discovery.

The surprise victory by Hinton’s group in the Merck contest clearly

showed the utility of deep learning in a field where few had expected it

to make an impact.

That’s not all. Microsoft’s Peter Lee says there’s promising early

research on potential uses of deep learning in machine

vision—technologies that use imaging for applications such as industrial

inspection and robot guidance. He also envisions personal sensors that

deep neural networks could use to predict medical problems. And sensors

throughout a city might feed deep-learning systems that could, for

instance, predict where traffic jams might occur.

In a field that attempts something as profound as modeling the human

brain, it’s inevitable that one technique won’t solve all the

challenges. But for now, this one is leading the way in artificial

intelligence. “Deep learning,” says Dean, “is a really powerful metaphor

for learning about the world.”

人工智慧 挑戰考大學、寫小說

〔編譯林翠儀/綜合報導〕日本經濟新聞報導,為開拓「人工智慧」的無限可能,日本研究人員計畫讓搭載人工智慧的電腦報考東京大學,還要讓電腦在5年後創作4000字的小說。

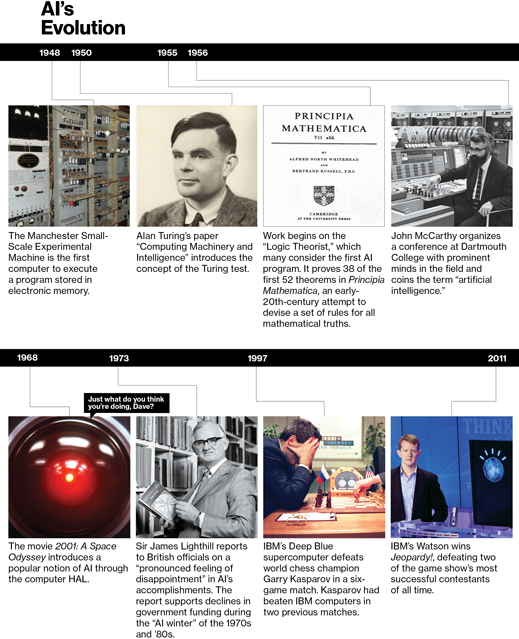

人工智慧又稱機器智能,通常是指人工製造的系統,經過運算後表現出來的智能。科學家從1950年代著手研究人工智慧,希望創造出具有智能的機器人成為勞動力,但成果仍無法跨越「玩具」領域。

1970年代,人工智慧的研究處於停滯狀態,直到1997年美國IBM電腦「深藍(Deep Blue)」,在一場6局對決的西洋棋賽中擊敗當時的世界棋王。2011年IBM的「華生(Watson)」參加美國益智節目贏得首獎百萬美元,人工智慧的開發再度受到矚目。

日本2010年也曾以一套將棋人工智慧系統打敗職業棋手,國立情報學研究所的研究員更異想天開,打算嘗試讓擁有人工智慧的電腦報考日本第一學府東京大學。

目

前該研究所和開發人工智慧軟體的富士通研究所合作,讓電腦試作大學入學考試的題目。研究人員表示,目前電腦大概能夠回答5到6成的題目,其中最難解的是數

學部分,因為電腦沒辦法像人類一樣,在閱讀問題的敘述文字後,馬上理解題意進行運算。不過,研究人員希望在2016年拿到聯考高分,2021年考上東大。

此外,人工智慧一向被認為「缺乏感性」,因此研究人員還嘗試挑戰用人工智慧寫小說,初步計畫讓電腦寫出長約4000字的科幻小說,並預定5年後參加徵文比賽。

Op-Ed Contributor

What Is Artificial Intelligence?

By RICHARD POWERS

Published: February 5, 2011

Illustrations by Vance Wellenstein

IN the category “What Do You Know?”, for $1 million: This four-year-old upstart the size of a small R.V. has digested 200 million pages of data about everything in existence and it means to give a couple of the world’s quickest humans a run for their money at their own game.

The question: What is Watson?

I.B.M.’s groundbreaking question-answering system, running on roughly 2,500 parallel processor cores, each able to perform up to 33 billion operations a second,

is playing a pair of “Jeopardy!” matches against the show’s top two living players, to be aired on Feb. 14, 15 and 16. Watson is I.B.M.’s latest self-styled Grand Challenge, a follow-up to

the 1997 defeat by its computer Deep Blue of Garry Kasparov, the world’s reigning chess champion. (It’s remarkable how much of the digital revolution has been driven by games and entertainment.) Yes, the match is a grandstanding stunt, baldly calculated to capture the public’s imagination. But barring any humiliating stumble by the machine on national television, it should.

Consider the challenge: Watson will have to be ready to identify anything under the sun, answering all manner of coy, sly, slant, esoteric, ambiguous questions ranging from the “Rh factor” of Scarlett’s favorite Butler or the 19th-century painter whose name means “police officer” to the rhyme-time place where Pelé stores his ball or what you get when you cross a typical day in the life of the Beatles with a crazed zombie classic. And he (forgive me) will have to buzz in fast enough and with sufficient confidence to beat Ken Jennings, the holder of the longest unbroken “Jeopardy!” winning streak, and Brad Rutter, an undefeated champion and the game’s biggest money winner. The machine’s one great edge: Watson has no idea that he should be panicking.

Open-domain question answering has long been one of the great holy grails of artificial intelligence. It is considerably harder to formalize than chess. It goes well beyond what search engines like Google do when they comb data for keywords. Google can give you 300,000 page matches for a search of the terms “greyhound,” “origin” and “African country,” which you can then comb through at your leisure to find what you need.

Asked in what African country the greyhound originated, Watson can tell you in a couple of seconds that the authoritative consensus favors Egypt. But to stand a chance of defeating Mr. Jennings and Mr. Rutter, Watson will have to be able to beat them to the buzzer at least half the time and answer with something like 90 percent accuracy.

When I.B.M.’s David Ferrucci and his team of about 20 core researchers began their “Jeopardy!” quest in 2006, their state-of-the-art question-answering system could solve no more than 15 percent of questions from earlier shows. They fed their machine libraries full of documents — books, encyclopedias, dictionaries, thesauri, databases, taxonomies, and even Bibles, movie scripts, novels and plays.

But the real breakthrough came with the extravagant addition of many multiple “expert” analyzers — more than 100 different techniques running concurrently to analyze natural language, appraise sources, propose hypotheses, merge the results and rank the top guesses. Answers, for Watson, are a statistical thing, a matter of frequency and likelihood. If, after a couple of seconds, the countless possibilities produced by the 100-some algorithms converge on a solution whose chances pass Watson’s threshold of confidence, it buzzes in.

This raises the question of whether Watson is really answering questions at all or is just noticing statistical correlations in vast amounts of data. But the mere act of building the machine has been a powerful exploration of just what we mean when we talk about knowing.

Who knows how Mr. Jennings and Mr. Rutter do it — puns cracked, ambiguities resolved, obscurities retrieved, links formed across every domain in creation, all in a few heartbeats. The feats of engineering involved in answering the smallest query about the world are beyond belief. But I.B.M. is betting a fair chunk of its reputation that 2011 will be the year that machines can play along at the game.

Does Watson stand a chance of winning? I would not stake my “Final Jeopardy!” nest egg on it. Not yet. Words are very rascals, and language may still be too slippery for it. But watching films of the machine in sparring matches against lesser human champions, I felt myself choking up at its heroic effort, the size of the undertaking, the centuries of accumulating groundwork, hope and ingenuity that have gone into this next step in the long human drama. I was most moved when the 100-plus parallel algorithms wiped out and the machine came up with some ridiculous answer, calling it out as if it might just be true, its cheerful synthesized voice sounding as vulnerable as that of any bewildered contestant.

It does not matter who will win this $1 million Valentine’s Day contest. We all know who will be champion, eventually. The real showdown is between us and our own future. Information is growing many times faster than anyone’s ability to manage it, and Watson may prove crucial in helping to turn all that noise into knowledge.

Dr. Ferrucci and company plan to sell the system to businesses in need of fast, expert answers drawn from an overwhelming pool of supporting data. The potential client list is endless. A private Watson will cost millions today and requires a room full of hardware. But if what Ray Kurzweil calls the Law of Accelerating Returns keeps holding, before too long, you’ll have an app for that.

Like so many of its precursors, Watson will make us better at some things, worse at others. (Recall

Socrates’ warnings about the perils of that most destabilizing technology of all — writing.) Already we rely on Google to deliver to the top of the million-hit list just those pages we are most interested in, and we trust its concealed algorithms with a faith that would be difficult to explain to the smartest computer. Even if we might someday be able to ask some future Watson how fast and how badly we are cooking the earth, and even if it replied (based on the sum of all human knowledge) with 90 percent accuracy, would such an answer convert any of the already convinced or produce the political will we’ll need to survive the reply?

Still, history is the long process of outsourcing human ability in order to leverage more of it. We will concede this trivia game (after a very long run as champions), and find another in which, aided by our compounding prosthetics, we can excel in more powerful and ever more terrifying ways.

Should Watson win next week, the news will be everywhere. We’ll stand in awe of our latest magnificent machine, for a season or two. For a while, we’ll have exactly the gadget we need. Then we’ll get needy again, looking for a newer, stronger, longer lever, for the next larger world to move.

For “Final Jeopardy!”, the category is “Players”: This creature’s three-pound, 100-trillion-connection machine won’t ever stop looking for an answer.

The question: What is a human being?

Richard Powers is the author of the novel “Generosity: An Enhancement.”