A voice recognition program translated a speech given by Richard F. Rashid, Microsoft’s top scientist, into Mandarin Chinese.

Using an artificial intelligence

technique inspired by theories about how the brain recognizes patterns,

technology companies are reporting startling gains in fields as diverse

as computer vision, speech recognition and the identification of

promising new molecules for designing drugs.

The advances have led to widespread enthusiasm among researchers who

design software to perform human activities like seeing, listening and

thinking. They offer the promise of machines that converse with humans

and perform tasks like driving cars and working in factories,

raising the specter of automated robots that could replace human workers.

Keith Penner

A student team led by the computer scientist Geoffrey E. Hinton used deep-learning technology to design software.

The technology, called deep learning, has already been put to use in

services like Apple’s Siri virtual personal assistant, which is based on

Nuance Communications’ speech recognition service, and in Google’s

Street View, which uses machine vision to identify specific addresses.

But what is new in recent months is the growing speed and accuracy of

deep-learning programs, often called artificial neural networks or just

“neural nets” for their resemblance to the neural connections in the

brain.

“There has been a number of stunning new results with deep-learning

methods,” said Yann LeCun, a computer scientist at New York University

who did pioneering research in handwriting recognition at Bell

Laboratories. “The kind of jump we are seeing in the accuracy of these

systems is very rare indeed.”

Deep learning was given a particularly audacious display at a conference last month in Tianjin, China, when

Richard F. Rashid,

Microsoft’s top scientist, gave a lecture in a cavernous auditorium

while a computer program recognized his words and simultaneously

displayed them in English on a large screen above his head.

Then, in a demonstration that led to stunned applause, he paused

after each sentence and the words were translated into Mandarin Chinese

characters, accompanied by a simulation of his own voice in that

language, which Dr. Rashid has never spoken.

The feat was made possible, in part, by deep-learning techniques that

have spurred improvements in the accuracy of speech recognition.

Dr. Rashid, who oversees Microsoft’s worldwide research organization,

acknowledged that while his company’s new speech recognition software

made 30 percent fewer errors than previous models, it was “still far

from perfect.”

“Rather than having one word in four or five incorrect, now the error

rate is one word in seven or eight,” he wrote on Microsoft’s Web site.

Still, he added that this was “the most dramatic change in accuracy”

since 1979, “and as we add more data to the training we believe that we

will get even better results.”

Artificial intelligence researchers are acutely aware of the dangers

of being overly optimistic. Their field has long been plagued by

outbursts of misplaced enthusiasm followed by equally striking declines.

In the 1960s, some computer scientists believed that a workable

artificial intelligence system was just 10 years away. In the 1980s, a

wave of commercial start-ups collapsed, leading to what some people

called the “A.I. winter.”

But recent achievements have impressed a wide spectrum of computer

experts. In October, for example, a team of graduate students studying

with the University of Toronto computer scientist

Geoffrey E. Hinton won the top prize in a contest sponsored by Merck to design software to help find molecules that might lead to new drugs.

From a data set describing the chemical structure of 15 different

molecules, they used deep-learning software to determine which molecule

was most likely to be an effective drug agent.

The achievement was particularly impressive because the team decided

to enter the contest at the last minute and designed its software with

no specific knowledge about how the molecules bind to their targets. The

students were also working with a relatively small set of data; neural

nets typically perform well only with very large ones.

“This is a really breathtaking result because it is the first time

that deep learning won, and more significantly it won on a data set that

it wouldn’t have been expected to win at,” said Anthony Goldbloom,

chief executive and founder of Kaggle, a company that organizes data

science competitions, including the Merck contest.

Advances in pattern recognition hold implications not just for drug

development but for an array of applications, including marketing and

law enforcement. With greater accuracy, for example, marketers can comb

large databases of consumer behavior to get more precise information on

buying habits. And improvements in facial recognition are likely to make

surveillance technology cheaper and more commonplace.

Artificial neural networks, an idea going back to the 1950s, seek to

mimic the way the brain absorbs information and learns from it. In

recent decades, Dr. Hinton, 64 (a great-great-grandson of the

19th-century mathematician

George Boole,

whose work in logic is the foundation for modern digital computers),

has pioneered powerful new techniques for helping the artificial

networks recognize patterns.

Modern artificial neural networks are composed of an array of

software components, divided into inputs, hidden layers and outputs. The

arrays can be “trained” by repeated exposures to recognize patterns

like images or sounds.

These techniques, aided by the growing speed and power of modern

computers, have led to rapid improvements in speech recognition, drug

discovery and computer vision.

Deep-learning systems have recently outperformed humans in certain limited recognition tests.

Last year, for example, a program created by scientists at the

Swiss A. I. Lab

at the University of Lugano won a pattern recognition contest by

outperforming both competing software systems and a human expert in

identifying images in a database of German traffic signs.

The winning program accurately identified 99.46 percent of the images

in a set of 50,000; the top score in a group of 32 human participants

was 99.22 percent, and the average for the humans was 98.84 percent.

This summer, Jeff Dean, a Google technical fellow, and Andrew Y. Ng, a

Stanford computer scientist, programmed a cluster of 16,000 computers

to train itself to automatically recognize images in a library of 14

million pictures of 20,000 different objects. Although the accuracy rate

was low — 15.8 percent — the system did 70 percent better than the most

advanced previous one.

One of the most striking aspects of the research led by Dr. Hinton is

that it has taken place largely without the patent restrictions and

bitter infighting over intellectual property that characterize

high-technology fields.

“We decided early on not to make money out of this, but just to sort

of spread it to infect everybody,” he said. “These companies are

terribly pleased with this.”

Referring to the rapid deep-learning advances made possible by

greater computing power, and especially the rise of graphics processors,

he added:

“The point about this approach is that it scales beautifully.

Basically you just need to keep making it bigger and faster, and it will

get better. There’s no looking back now.”

信陵君曰:

信陵君曰: 無忌謹

無忌謹

文選˙任昉˙到大司馬記室牋:

文選˙任昉˙到大司馬記室牋:

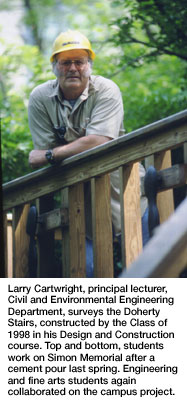

This year's project—a memorial to the late professor and Nobel laureate Herbert A. Simon—just started, like Cartwright's class, on Jan. 14.

This year's project—a memorial to the late professor and Nobel laureate Herbert A. Simon—just started, like Cartwright's class, on Jan. 14.  "I really like this course. It's a lot of fun. It's not your typical class because you actually get to design something. There's not a set class period when you have to go to a lecture. It's pretty much student-run. Larry does a lot of the advising. Everything that we use has already been taught to us. We apply it. A lot of us don't know that much about construction. It's an eye opener."

"I really like this course. It's a lot of fun. It's not your typical class because you actually get to design something. There's not a set class period when you have to go to a lecture. It's pretty much student-run. Larry does a lot of the advising. Everything that we use has already been taught to us. We apply it. A lot of us don't know that much about construction. It's an eye opener." "Even if it's just a bunch of students digging with shovels, Larry [Cartwright] is always looking to teach and provide real-world know-how. It's always a test, except this time the teacher's wearing a hard-hat. It's extremely helpful for those who go into design or construction because it shows the critical link between the two by requiring students to participate in both. There was always the opportunity to step up, take on more responsibility and enhance the final product. Even if students choose different career paths than design/construction, they learn more about responsibility in group settings and have a sense of pride knowing that they left a permanent fixture at an important place in their lives.

"Even if it's just a bunch of students digging with shovels, Larry [Cartwright] is always looking to teach and provide real-world know-how. It's always a test, except this time the teacher's wearing a hard-hat. It's extremely helpful for those who go into design or construction because it shows the critical link between the two by requiring students to participate in both. There was always the opportunity to step up, take on more responsibility and enhance the final product. Even if students choose different career paths than design/construction, they learn more about responsibility in group settings and have a sense of pride knowing that they left a permanent fixture at an important place in their lives.  "Design and Construction was, by far, the best course I took at Carnegie Mellon. It combined book knowledge from four years of classes, a tremendous amount of teamwork and hands-on work. The class learned to work with students of different disciplines including art majors, architects and engineers. This was my first exposure to a true interdisciplinary project.

"Design and Construction was, by far, the best course I took at Carnegie Mellon. It combined book knowledge from four years of classes, a tremendous amount of teamwork and hands-on work. The class learned to work with students of different disciplines including art majors, architects and engineers. This was my first exposure to a true interdisciplinary project.  "Design and Construction was the course I enjoyed the most. It took a lot of time and effort but was well worth the long hours and labor. To be so heavily involved in the direction of the course and project is something that you just don't get every day at any institution. The course was so well thought-out and planned that it made you look forward to having class and working. It was more fun than work, which is a rarity these days.

"Design and Construction was the course I enjoyed the most. It took a lot of time and effort but was well worth the long hours and labor. To be so heavily involved in the direction of the course and project is something that you just don't get every day at any institution. The course was so well thought-out and planned that it made you look forward to having class and working. It was more fun than work, which is a rarity these days.  "We've all heard horror stories from past seniors, but in the end Design and Construction was a great experience. It was hard work, but we learned so much about actually building something rather than just drawing it on paper. It was a huge bonding experience for our class. It didn't seem so much like work as it did like just hanging out and having a good time. When it was finished, it was such a good feeling to sit back and think I helped to build that.

"We've all heard horror stories from past seniors, but in the end Design and Construction was a great experience. It was hard work, but we learned so much about actually building something rather than just drawing it on paper. It was a huge bonding experience for our class. It didn't seem so much like work as it did like just hanging out and having a good time. When it was finished, it was such a good feeling to sit back and think I helped to build that.  Engineering students expect to enjoy a Larry Cartwright course, and they learn from it. Besides the Design and Construction course that has resulted in engineers with a firm grasp on reality, not to mention the addition of so many cozy corners on campus, the professor is known for his Civil and Environmental Engineering Design course, which he teaches with other faculty.

Engineering students expect to enjoy a Larry Cartwright course, and they learn from it. Besides the Design and Construction course that has resulted in engineers with a firm grasp on reality, not to mention the addition of so many cozy corners on campus, the professor is known for his Civil and Environmental Engineering Design course, which he teaches with other faculty.